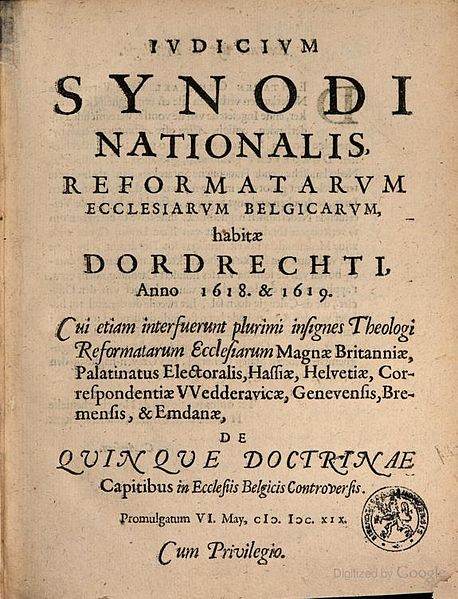

The Synod of Dordt, 1618-1619

Welcome to the Synod of Dordt web pages! The Meeter Center for Calvin Studies at Calvin University has brought together a vast array of materials and information about the Synod of Dordt and its impact.

Scroll down for a very short introduction to the synod. Click on the boxes below to find out more about the main participants in the synod, key dates, the synod-sponsored major Bible translation project known as the Statenvertaling, and links to further resources. We hope these pages will help individuals, churches, and other groups learn more about the synod as we commemorate the 400th anniversary of its gathering.

Who’s Who

Learn about the major characters at the Synod of Dordt.

Timeline

Browse a timeline of events from the beginning of the Reformation to the publication of the Statenvertaling Bible.

The Statenvertaling Bible

Read about the publication of the first full translation of the Bible into Dutch from its ancient sources.

Further Information

Find links to upcoming conferences and exhibits and resources for further reading about the Synod of Dordt.

A (very) brief historical introduction

Synod of Dort, Dordt, or Dordrecht: which is right? In fact, all three are correct. Dordrecht is the name of the Dutch city in the province of Holland that hosted the synod. The colloquial name for Dordrecht in Dutch is Dordt. The English version of Dordt is Dort. For the sake of consistency, and to match the usage of the majority of scholars writing about the synod, we will refer to the Synod of Dordt.

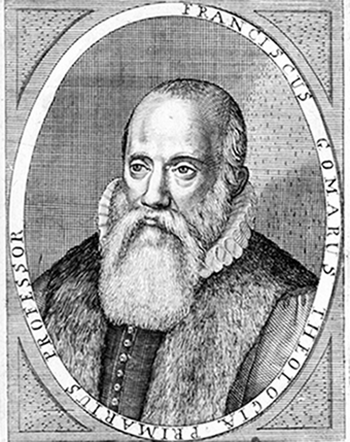

The Reformations of the sixteenth century led to the emergence of different confessional groups within western Christendom: Lutherans, Anglicans, Anabaptists, and Reformed believers (including Huguenots in France and Presbyterians in Scotland) each made their case for their beliefs over against Roman Catholicism and each other. But some major theological issues remained unresolved all the way up to the seventeenth century. Within the Reformed family of faith, theologians disagreed over the doctrine of election: did God will to save all, or only some from eternal damnation? Did people have free will in their decision to turn towards or away from salvation? Did God’s foreknowledge of how people would respond to the gift of salvation in Jesus Christ affect God’s decision to number them among the elect or the reprobate? In the Dutch Reformed church, this controversy crystallized in a contentious debate between two professors at the University of Leiden, Jacobus Arminius and Franciscus Gomarus. Arminius (and his supporters after his death in 1609) taught that the idea of God electing and reprobating everyone even before Adam and Eve’s fall into sin was unbiblical and left no room for God’s grace to act in human lives. His supporters issued a Remonstrance in 1610, listing their five points of disagreement with their opponents. Gomarus for his part held to a strict view of predestination and election. He and his supporters became known as the Counter-Remonstrants.

This theological controversy overlapped with a political power struggle in the Netherlands in the first decades of the seventeenth century. Two factions, one led by Prince Maurice of Nassau and the other led by the senior Dutch politician Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, vied for control of the Dutch government. Maurice of Nassau increasingly allied himself with the traditionalist Calvinist theologians (the Counter-Remonstrants), whereas Oldenbarnevelt found his support among the more liberal wing (the Remonstrants). The two groups also crucially divided over the appropriateness of state oversight and intervention in church affairs. Remember that the Reformed faith was the official faith of the Netherlands at the time, and hence the Reformed church functioned as a state church. However, the Counter-Remonstrants largely rejected what they saw as the state’s encroachment on the church, whereas the Remonstrants appealed to the state to exercise its authority over the church (and curb the pressure of their opponents).

,_by_workshop_of_Michiel_Jansz_van_Mierevelt2.jpg?language_id=1)

Theological debates and political pressures merged in 1618, leading the Dutch States-General (the Netherlands’ governing body) to call a national synod to resolve many of these issues. In order to give the meeting more legitimacy and impact, the States-General decided to invite Reformed delegates from other countries to join the gathering. On November 13, 1618, the Synod of Dordt began its meetings. The final session took place on May 9, 1619.

Results of the Synod

The Synod of Dordt is most well known for its theological work on election and predestination, resulting in the Canons of Dordt and the ensuing decision to dismiss Remonstrant pastors from their posts and banish them from Dutch territory. However, the Synod of Dordt also took time to address a number of other issues.

Summary of some of the Synod’s other decisions

- Baptism of non-Christian servants and slaves in the Dutch East Indies. The Synod considered whether these individuals should be baptized if their parents were not Christian. Ultimately, the delegates decided that adult servants and slaves who requested baptism and were catechized could be baptized, but that child servants and slaves who had non-Christian parents could not be baptized until they were old enough to be catechized and request the sacrament.

- Bible translation. The Synod commissioned the Statenvertaling (States Translation), the first complete Dutch Bible translation working from the original languages. In a joint effort of church and state, the Bible was funded by the States General, the governing body of the Dutch Republic.

- Catechisms and catechizing. After extensive debate, the Synod ordered three kinds of catechizing: at home, at school, and at church, and created a committee to prepare appropriate catechisms for each setting and age group, all based on the Heidelberg Catechism.

- Church order. The Synod spent considerable time after the departure of the international delegates setting up a uniform church order that would apply to all Dutch and Walloon (French-speaking) Reformed churches. The church order dealt with the roles and responsibilities of pastors, elders, and deacons, outlined the structure and operations of representative church assemblies all the way up to the national synod, provided directions for catechetical instruction and the celebration of the sacraments, and laid out the practice of church discipline. Read an English translation of this church order.

- Patronage. the Synod of Dordt recognized the continuing practice of patrons (usually members of the nobility) having the right to nominate clergy for particular churches, but laid out nine rules to regulate the practice, including allowing the patron a maximum time of two to three months to nominate a candidate for a vacancy, after which time they would lose their right to make that nomination this time round.

- Sabbath observance. The Synod of Dordt approved a set of six articles calling for people to forego work on the Sabbath, though the articles do not lay out specific provisions for how the Sabbath should be observed.

- Schools and education. The Synod of Dordt approved a series of ten articles to regulate higher education in the Dutch academies and universities. These included ensuring strong confessional oversight of the teaching faculty, preventing the professors in philosophy and languages from discussing theological topics without permission of the theology professors, and keeping theology professors from raising doubts about received doctrines or articulating new theological opinions.

- Training for student pastors. The Synod decided that those training for the ministry were not to celebrate baptisms, but that local classes and churches could decide for themselves whether or not to allow the students to preach.