- Joseph Alleine

Joseph Alleine was born in 1634 in Wiltshire, England. He began his studies at Oxford in 1649, receiving his Bachelor of Divinity in 1653. He then became a tutor and chaplain at Corpus Christi College in Oxford. He became an assistant to George Newton, vicar of St. Mary Magdalene parish church in Taunton, Somerset in 1655; at this time he also married his cousin, Theodosia Alleine, daughter of Richard Alleine.

Ejected from his parish during The Uniformity Act of 1662, Alleine subsequently began to travel around preaching, along with his fellow ejected minister John Westley, resulting in his being jailed in 1663 at Ilchester. He was released on May 26, 1664.

When the 1665 Five Mile Act was passed, Joseph and Theodosia moved to the nearby town of Wellington. He was subjected to continued harassment, however, and eventually returned to Taunton, where he was arrested again in 1665 for holding a conventicle.

He died in 1668, and was buried in St Mary’s chancel, in accordance with his wish to be buried at Taunton.

Alleine was a passionate preacher, and was noted by the Puritan poet Richard Baxter for his effective and well-wrought sermons. He was also a prolific writer who produced many tracts and treatises, but the most widely known is An Alarm to the Unconverted (1671), later published as A Sure Guide to Heaven (1675). This work was also published in Scotland and North America, and has been translated into Welsh and German.

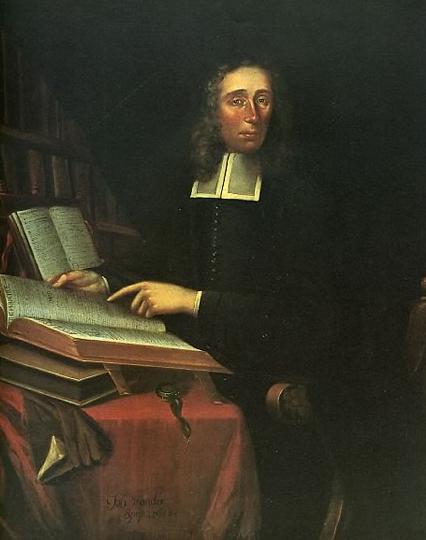

- Richard Alleine

Richard Alleine was born in 1611, in Somersetshire, England. His father was a rector, and he tutored the boy. Richard attended Oxford University beginning at age nineteen, and eventually earned both B.A. and M.A. degrees there. He was ordained as a priest in 1634, and was later appointed as chaplain to Sir Ralph Hopton. He served as vicar at Batcombe in Somersetshire for twenty years, but was forced from that post during the Great Ejection in 1662, when 2,000 Puritan ministers were removed from their positions after Charles II was restored to the throne. This, and the subsequent publication of the Five Mile Act, precipitated his departure to a nearby village (Frome Selwood). He continued to preach in private homes for the remainder of his life, and died in 1681.

Alleine was an articulate proponent of Puritan doctrine, and a supporter of the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643. He published many instructional and inspiring works for believers, several of which are still in print today. Heaven Opened: The Riches of God’s Covenant, or A Brief and Plain Discovery of the Riches of God’s Covenant by Grace was published in London in 1665. His Vindiciæ Pietatis was published without license, which was common for nonconformist works of this period, and copies sold quickly. The king’s printer consigned it to be destroyed, but then later brought back the pages intended for destruction and printed and sold them in his own bookshop.

Several of his works are available to read online at the Post Reformation Digital Library.

- William Ames

William Ames was born in 1576 in Suffolk, England to a merchant family. His parents died when he was still young, and he was raised by his uncle Robert Snelling, who was a Puritan.

William was educated at Christ’s College at Cambridge University, where he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1598, and a Master of Arts degree in 1601. That same year he was elected as a fellow at Christ’s College. During this period, he became strongly influenced by the preaching of William Perkins.

In 1609, he lost out on a mastership appointment because of his Puritan sympathies. Then on December 21, he preached a fiery sermon denouncing gambling, and was taken into custody. His academic degrees were revoked and he was suspended from his ecclesiastical duties.

He resigned his fellowship and soon afterward left for the Netherlands. There he developed a reputation as a skilled theologian, and served as chief advisor to Johannes Bogerman during the Synod of Dordt.

He was appointed professor of theology at Franeker University in Friesland in 1622. Many students from around Europe came to study with him. While there he wrote two of his most-notable works: Medulla Theologiae (The Marrow of Theology) and De conscientia (Of the Conscience).

In 1632 he co-pastored a church in Rotterdam with Hugh Peter. Peter wanted him to help found a Puritan college in that city, but in 1633 Ames’s house in Rotterdam was flooded, which may have precipitated his death from pneumonia later that year.

Image of William Ames is in the public domain {{PD-US}}.

- Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter was born in 1615 in Shropshire England to Richard Baxter Sr. and Beatrice Adney. His education was largely informal, though he did attend Wroxeter grammar school for a time.

He studied theology on his own and was ordained as a deacon in the Church of England at age 23, and served at a parish in Kidderminster from 1641-1660, where his sermons became so popular that the church was enlarged to accommodate the crowds who attended them. He also became a chaplain in the Parliamentary army in 1645.

He resisted the authoritarian tendencies of the Church of England at this time, and eventually registered as a Nonconformist, but also opposed the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643. He warned against what he saw as an antinomian strain in the doctrine of salvation by faith alone, and to refute this doctrine he wrote Aphorisms of Justification (1649). Aphorisms described salvation as a combination of human agency and divine grace-- a soteriology which pleased neither Calvinists nor Arminians.

In 1660 he was offered the bishopric of Hereford but declined it, and in 1662 was ejected from the Church of England, under the Act of Uniformity. He married Margaret Charlton when he was 49, and they settled in London. He was imprisoned several times, lastly in 1685 for sedition. He died in 1691.

Baxter wrote prolifically, and among his bestselling works is the devotional The saints’ everlasting rest (1650). His posthumously published Reliquiae Baxterianae (1696) remains a major resource for historians of the period.

Image of Richard Baxter is in the public domain {{PD-US}}.

- William Bradford

William Bradford was born in 1590 in Yorkshire, England. He was orphaned at an early age. At seventeen he joined a Puritan Separatist congregation, and relocated with that group to the Netherlands, moving to Amsterdam in 1607 and to Leiden in 1608.

In 1611 Bradford became a weaver. He married Dorothy May in 1613, with whom he had one child. In 1620 he and his wife joined the journey of a group of separatists to the east coast of North America on board the Mayflower in 1620. However, Dorothy fell overboard and drowned in Provincetown Harbor. Bradford married Alice Carpenter Southworth in 1623.

Once ashore, Bradford became governor to the young colony of Plymouth after the first governor died. As governor, he negotiated trade agreements with the Wampanaog tribe, and, along with seven other colonists, took on the colony’s debts in 1627, as part of an arrangement with the merchant investors who had helped fund the enterprise.

His history of the Plymouth colony, Of Plymouth Plantation (1646) is of great value to historians of the early America and the Plymouth colony. He died in 1657.

- Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet was born in Northampton, England in 1612. Her father, Thomas Dudley, educated her at home, where she was tutored in languages, music and dancing. She also read widely from books in the library of the Earl of Lincoln’s estate, where Dudley was steward.

At sixteen, Anne married her father’s assistant Simon Bradstreet, and in 1630, the couple left for the colonies, along with Anne’s parents. Life there frequently featured illness, hunger, and the threat of attacks by Native Americans, and Anne struggled to adapt to the contrast between the old world and the new.

Anne and Simon had eight children, and she juggled many household duties. Nevertheless, she found time to write poetry, often at night while her family slept. She became the first published female poet in America when her brother-in-law in England published a collection of her early poems, titled The Tenth Muse, Lately Sprung Up in America (1650). Her later poems have received critical acclaim, especially “Contemplations,” posthumously published in 1678.

However, women at this time were expected to limit their achievements to the domestic sphere, and those who rebelled against this situation often faced steep penalties. Anne’s poetry addressed these limitations, but also the joys of family life, including love poems to her husband. Her work displays a deep devotion to God and faith in the face of many struggles, highlighting the inner intellectual and emotional life of a woman who was also a devout Puritan.

She died of tuberculosis in 1672.

Image of Anne Bradstreet is in the public domain {{PD-US}}.

- John Bunyan

John Bunyan was born in 1628 in Bedfordshire, England to a tinker and his wife. He did not undergo much formal education but became a prolific author and popular preacher.

At 21, Bunyan married a woman whose only dowry was two pious books, The Plain Man’s Pathway to Heaven (Arthur Dent) and The Practice of Piety (Lewis Bayly). These books influenced him to greater devotion to God, but he questioned some of the worship practices in the Church of England. He began attending a Separatist church in Bedford, and soon was a popular lay preacher there.

In 1660 he was arrested for preaching illegally. He refused to stop preaching if released, and subsequently spent twelve years imprisoned, although during this time he was occasionally allowed to continue writing, and to leave prison temporarily to preach.

In May 1672 he was released and began his appointment as pastor to his Bedford church, which he had been granted in January of that same year.

A few years later he was jailed again for preaching. While in prison, he began work on his most famous book, The Pilgrim’s Progress, which went on to become one of the best-selling books ever written, excepting only the Bible and Thomas Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ.

He was freed on June 21, 1677 and spent the remainder of his life ministering to nonconformist believers. He died in 1688. In all, he published sixty works, which were subsequently published in a three-volume set, The Works of John Bunyan.

Image of John Bunyan is in the public domain {{PD-US}}.

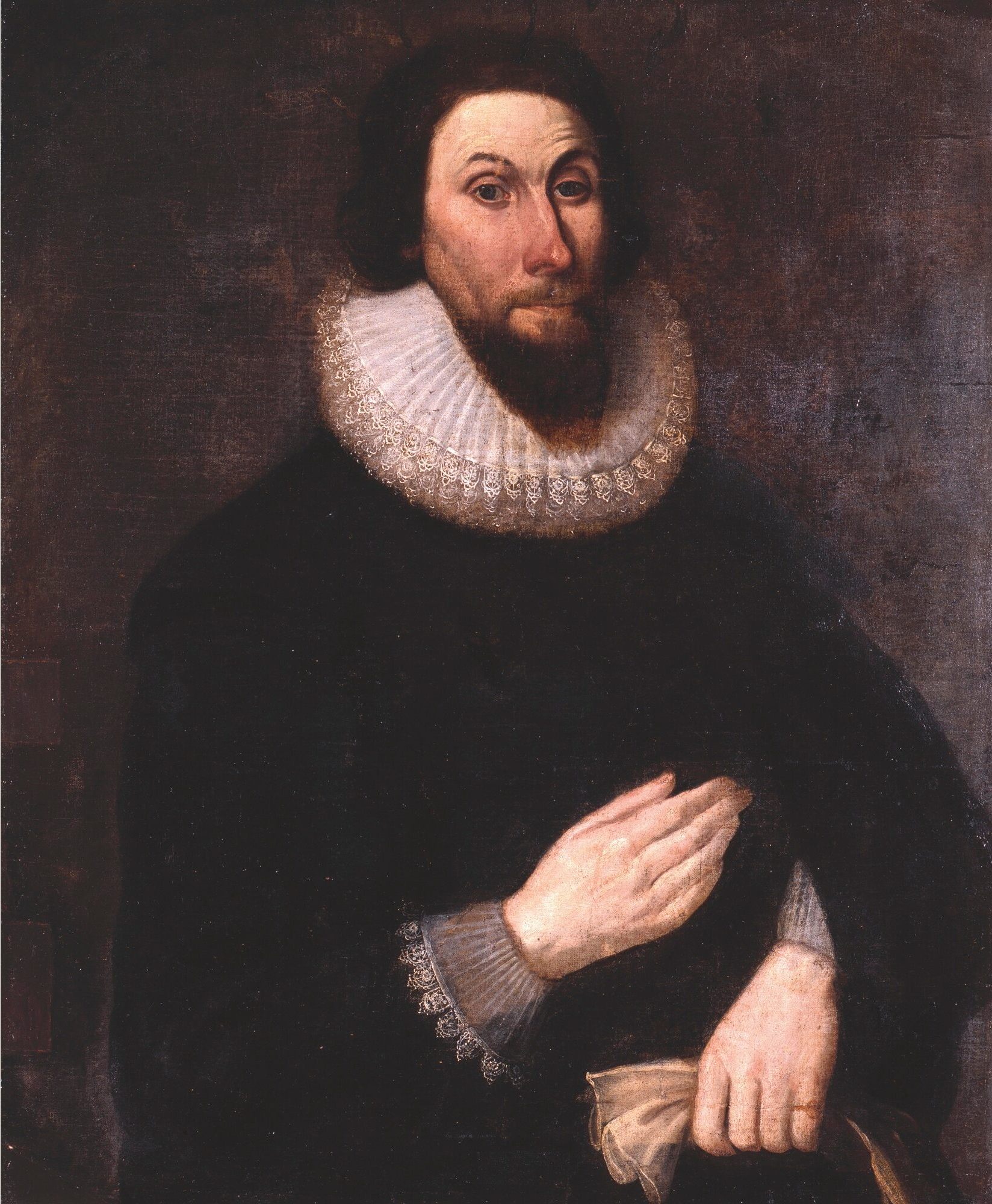

- John Cotton

_.jpg?language_id=1)

Born in Derbyshire, England in 1585, the son of lawyer Roland Cotton, John Cotton studied at Cambridge. He earned his Master of Arts and Bachelor of Divinity degrees at Emmanuel College.

In 1612 he was appointed Vicar of St. Boltoph’s in Lincolnshire. Despite his Puritan sympathies, he continued there until 1632, when he was summoned to the Court of High Commission. He did not appear at the court, and shortly thereafter resigned. He and his wife left secretly for Massachusetts Bay in 1633.

Cotton began preaching at the First Church of Boston soon after arriving in Massachusetts and continued preaching there until his death in 1652. He was an influential figure in the life of the colony. He testified at Anne Hutchinson’s trial during the Antinomian Controversy. His testimony initially exonerated her, but as the trial progressed he rejected her view that Christians’ conduct does not reflect their spiritual condition. He favored the integration of church and state and was instrumental in the expulsion of Roger Williams. He helped to produce the Cambridge Platform of church government for Congregational churches in New England.

Cotton wrote prolifically on church government. His work provides an important record of early Congregational ecclesiology. He also produced a short catechism for children titled Milk for Babes. Drawn out of the Breasts of Both Testaments. (1646), which later appeared in The New England Primer under the title Spiritual Milk for Boston Babes, and is regarded as the first children’s book published in America.

Image of John Cotton is in the public domain {{PD-US}}.

He was freed on June 21, 1677 and spent the remainder of his life ministering to nonconformist believers. He died in 1688. In all, he published sixty works, which were subsequently published in a three-volume set, The Works of John Bunyan.

- Mary Dyer

Mary Barrett was born in 1610 or 1611, in England. She married William Dyer in 1633, and the couple emigrated to America in 1634 or 1635. There, Mary supported the antinomian views of Anne Hutchinson. In 1637, Mary gave birth to a stillborn baby with significant birth defects. The birth was considered proof of the heretical nature of her antinomian views. In 1638, the Dyers followed Anne Hutchinson to Rhode Island, where William helped found the Portsmouth colony.

Mary and William returned to England in 1652, where Mary became a Quaker, joining the Society of Friends after hearing George Fox preach. William returned to New England in 1652, but Mary remained in England until 1657, when she traveled to Boston to protest a law banning Quakers from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and from Connecticut. She began traveling around the colonies to expound her Quaker beliefs in defiance of the law.

She was imprisoned in Boston in 1657 and expelled from New Haven in Connecticut in 1658. After another brief imprisonment in Boston in 1659, she was banished that September. However, she returned to Boston in October, and was subsequently condemned to be hanged. Her son and the governors of Connecticut interceded on her behalf, and she was granted a reprieve, but was again expelled.

Impelled by her convictions, she chose to return to Boston in May 1660, and this time she was hanged on June 1st.

Her execution is credited with having influenced the mitigation of anti-Quaker laws.

Image of Mary Dyer is in the public domain {{PD-US}}.

- Brilliana Harley

Brilliana Harley was born in Brill, the Netherlands, around 1598. Her father, Sir Edward Conway, served as governor of the Dutch city during its period under English control, in exchange for English assistance to the Dutch during the Dutch Revolt against Spain. The family returned to England in 1606.

In 1623 Brilliana married Sir Robert Harley, a Member of Parliament. She was his third wife, and they had seven children together. Harley held devout Puritan views, which Brilliana entirely shared. Notably, in 1640 and 1641, she gathered information for the House of Commons committee on “scandalous ministers,” namely clergy who supported the Royalists.

She also wrote many letters to her husband and to her son Edward, of which some 375 have been preserved. These letters provide a rich and detailed perspective on her life and concerns as a Puritan woman living during the English Civil War. The letters include some written during the siege of Brampton Bryan Castle, which was the Harley family home in Herefordshire.

At the time of the attack she was staying at Brampton with her youngest children and a small garrison, while Sir Robert remained in London at Parliament. Then in July of 1643 Royalist troops laid siege to Brampton Bryan Castle. Brilliana remained there and directed the defense of the castle for six weeks, after which the attackers were called away to assist Royalist forces at Gloucester.

It is believed the difficulties of life under siege weakened her health, which had never been robust. She died in October 1643.

Image of Brilliana Harley used under Creative Commons licensing: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Margaret Hoby

Margaret Hoby was born in 1571 to Arthur Dakins and Thomasine Gye, in Yorkshire England. She was the only heir to a landed estate.

She attended a school run by Katherine Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, where the daughters of wealthy Puritans were educated. Countess Hastings was the youngest surviving daughter of Lady Jane Grey and John Dudley of Northumberland.

She was married and widowed twice, and then wed Sir Thomas Posthumous Hoby at the age of twenty-five. They did not have any children.

Margaret kept a diary from 1599 to 1605, the earliest known diary written in English by a woman. The diary recounts her prayers, her scripture reading, and her earnest theological conversations with Puritans and non-Puritans alike.

Though focused mainly on her religious observances, the diary records a little bit about her other activities. She helped to manage her husband’s estate and tended to the sick in her household. Among other things, she enjoyed being in her garden and playing the orpharion, a stringed instrument which is like a lute. Her health was not always good, and she struggled with kidney stones, sensitive digestion, headaches, and other ailments. She viewed the plague to be a form of divine judgment and wrote that she hoped that episodes of the plague in England would cause the people to turn to God. Her diary gives a glimpse into her point of view, her religious practices, and to some extent, her daily life.

She died in 1633.

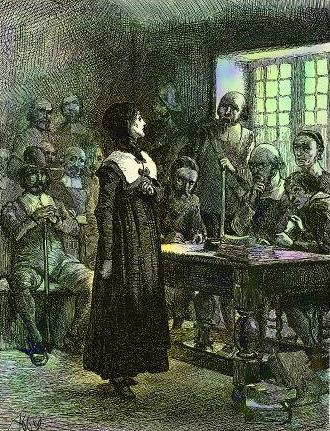

- Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson was born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1591, the child of Anglican minister Francis Marbury. Marbury, who had strong Puritan sympathies, was jailed for two years on charges of heresy in 1578, and began a three-year term of house arrest the year of Anne’s birth.

Anne married William Hutchinson in 1612, and worked as a midwife and herbalist while also teaching Bible study classes for women. She promoted the teachings of John Cotton, which challenged the Puritan teaching that the salvation of the elect is revealed through their works.

The Hutchinsons moved to Boston, Massachusetts in 1634, where Anne worked as a midwife, and held regular theological discussion groups for women and men. She taught that grace is a gift, not affected by behavior, clashing with the Puritan expectation that one’s election would be made visible in one’s deeds. Her outspoken views embroiled her in the Antinomian Controversy in Massachusetts, which resulted in the founding of Harvard College in 1636, to ensure that future ministers were educated in line with orthodox theology.

In 1637, Anne was tried in the General Court, where Governor John Winthrop and her former mentor John Cotton testified against her. She was declared a heretic and banished from the Massachusetts colony, remaining under house arrest until 1638, when she and her family left for Rhode Island territory.

After her husband’s death, she moved with her children to New Amsterdam on Long Island Sound. In 1643, Anne was among fifteen people who were killed in an attack by members of the Siwanoy tribe.

Image of Anne Hutchinson is in the public domain {{PD-US}} .

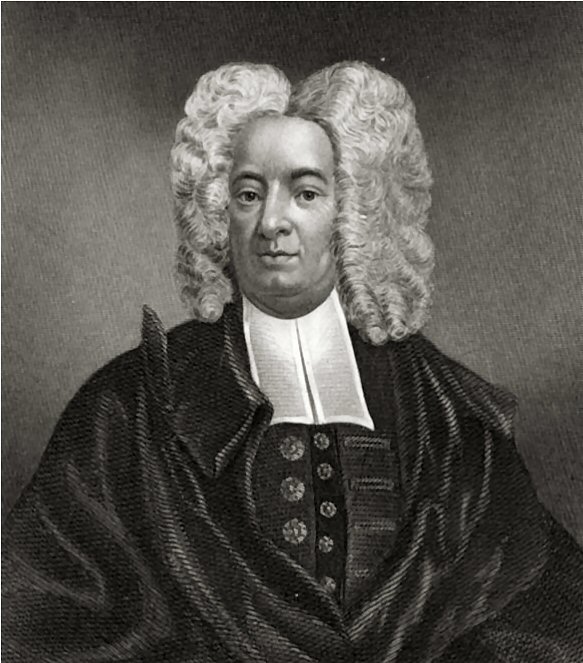

- Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather was born in Boston Massachusetts in 1663. He was the son of Increase Mather, and grandson of John Cotton.

Mather entered Harvard at age eleven or twelve and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree at age fifteen. Three years later he got his Master of Arts degree there as well. After overcoming a speech impediment, he was ordained as a minister in 1685 and began preaching at North Church in Boston at age seventeen. He eventually became the primary pastor there after his father’s death in 1723.

He was married three times and sired fifteen children, but two of his of his wives and thirteen of his children predeceased him.

His views on the importance of unity between different Christian denominations led him to participate in the ordination of a Baptist minister in 1718, which was considered scandalous for a Congregationalist at the time.

He produced 469 written works in his lifetime. His Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcraft and Possessions (1689) contributed to the fervor of the Salem Witch Trials in 1692, and he thereafter wrote a defense of the trials, entitled The Wonders of the Invisible World (1692). His Magnalia Christi Americana (1702), subtitled The Ecclesiastical History of New-England, from its first planting in the year 1620 until the year of Our Lord, 1698, remains an important resource for historians today.

He died in 1728.

Image of Cotton Mather is in the public domain {{PD-US}} .

- Increase Mather

Increase Mather was born in 1639 in Massachusetts. His father was the Puritan minister Richard Mather. He entered Harvard College at age twelve, received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1656, and his Master of Arts degree from Trinity College in Dublin in 1658.

Mather preached his first sermon on his eighteenth birthday and continued preaching in England and in Guernsey until 1661, when he returned to Massachusetts. He then married Maria Cotton, daughter of John Cotton, in 1662. One of their ten children was Cotton Mather. In 1664 Increase answered a call to pastor Second Church in Boston, where he remained as minister for the rest of his life.

In 1690 Mather became the official agent of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In his role as representative of the colony’s interests, he petitioned King James II of England for a new charter to replace the one which the king had revoked in 1686. The new charter was granted in 1692.

Mather’s Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits (1693) argued against the use of spectral evidence in the Salem witch trials of 1692 and 1693. This type of testimony involved witnesses who claimed that the accused visited them in their dreams. Mather remained supportive of the trials themselves but his opposition to spectral evidence precipitated their dismissal.

He was appointed president of Harvard College in 1685 but maintained his ministry at the Second Church. In 1701, the College presented him with a choice between continuing his ministry at the church or moving to Cambridge to live and retaining the presidency. He resigned the presidency later that year.

Mather died in 1723.

Increase Mather image is in the public domain {{PD-US}} .

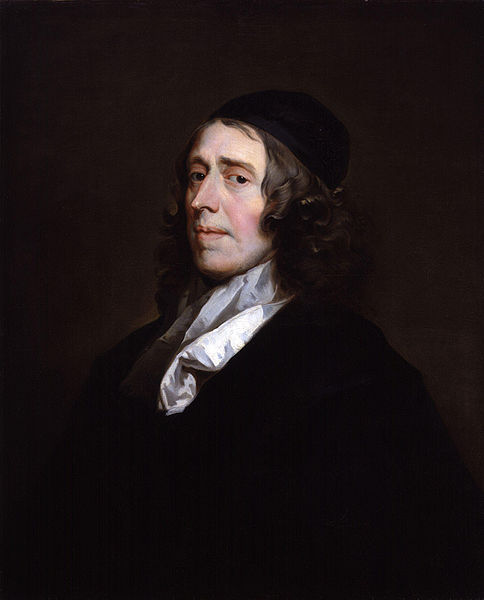

- John Owen

John Owen was born in Stadham, England in 1616. His father was a Puritan vicar.

Owen began attending Queen’s College, Oxford at age twelve. He obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1632 and his Master of Arts degree in 1635. After graduation he spent some years as a private tutor and chaplain for Sir William Dormer of Ascot and Sir John Lord Lovelace in Berkshire.

He published A Display of Arminianism in 1643 and was subsequently appointed rector at Fordham parish in Essex. In 1646, he became the vicar at St. Peter’s in Coggeshall.

Owen preached at Parliament the day after the execution of Charles I, after which Oliver Cromwell made him an army chaplain and brought him to Dublin to help manage affairs at Trinity College for a time. Under Cromwell, Owen was appointed to the deanship of Christ Church, Oxford in 1651, and then served as Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University from 1652 to 1657.

Oliver Cromwell’s son Richard became Chancellor of Oxford in 1660, appointing a Presbyterian as the new dean of Christ Church. Owen then retired to his home in Stadham and continued preaching there and in London. He died in 1683.

Owen remains one of England’s most important Calvinist theologians, and he contributed a significant body of work to Reformed theology. Notably, he defended Calvinism against Arminianism in The Death of Death in the Death of Christ (1647), and wrote a discourse on the Holy Spirit entitled Pneumatologia (1674). Many of his works are contained in the sixteen-volume set The Works of John Owen (1968).

John Owen image is in the public domain {{PD-US}}.

- William Perkins

William Perkins was born in 1558 in Warwickshire, England. He attended Christ’s College at Cambridge University, earning his Bachelor’s degree in 1581 and his Master’s degree in 1584, when he became a fellow there. He underwent a conversion experience while a student and switched from studying mathematics to studying theology. In 1585, he was appointed lecturer (or preacher) at the Church of St. Andrew the Great in Cambridge.

Perkins did not believe that those who wanted to see further reform should separate from the Church of England but he did object to certain Anglican practices, such as kneeling during the Eucharist. He argued for the doctrines of double predestination and limited atonement in his De Praedestinationis Modo et Ordine (1598) and God’s Free Grace and Man’s Free Will (1602).

He also addressed the question of how the elect were to become sure of their election and believed that sanctification was the surest sign that a person was saved. His Discourse of Conscience (1606) and The Whole Treatise of the Cases of Conscience (published posthumously in 1606), examined cases of conscience in this light.

He was a popular speaker and an influential theologian at home, in Europe and in New England. John Cotton* credited him as the reason Cambridge produced so many excellent preachers. By the time of his death, his works were purchased more frequently than those of John Calvin. Some of these were translated into Spanish, French, Italian, Czech, Irish, Welsh and Hungarian, and at least fifty editions were printed in Switzerland and in Germany.

He died from kidney stone complications in 1602.

William Perkins image is in the public domain {{PD-US}} .

- Mary Vere

Mary Vere was born in 1580 into a family with strong Puritan sympathies. One of her ancestors, William Tracy, was mentioned in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs and had been posthumously burnt at the stake over the contents of his will, which were declared heretical by Archbishop Warham in 1532. Her niece was Brilliana Harley, the devoted Puritan wife who defended her home against a siege by Royalist forces in 1643. Vere first married William Hoby but after his death she married Sir Horace Vere, who commanded English forces in the Netherlands.

Vere’s social standing and religious beliefs combined to make her a helpful patroness of Puritan ministers. She effected the appointment of several Puritan clergymen to parishes in Essex, including John Davenport, who eventually moved to New England and helped to start the New Haven Colony. In addition to helping Puritan clergy get livings, she was a source of encouragement and support to them. She maintained correspondence with several well-known pastors of the time, such as Nicholas Byfield and John Dod. William Gurnall, an Anglican cleric, dubbed her “Deliciae Cleri, the Ministers Delight.” Her influence also extended to those within her household, where she faithfully observed Puritan modes of worship along with daily Scripture reading and prayer.

William Gurnall preached her funeral sermon, entitled The Christian’s Labour and Reward, which was later included in Samuel Clarke’s Lives of sundry eminent persons in this later age (1683). She died in 1670.

Mary Vere (née Tracy), Lady Vere

by Frederick Hendrik van Hove

line engraving, circa 1683

NPG D28117

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ - John Winthrop

John Winthrop was born in 1588 in Suffolk, England to a family of the landed gentry. He enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1601 but left school to marry his first wife in 1603. After she died he married twice more, fathering sixteen children over his lifetime.

Winthrop was a devout Christian of strong Puritan convictions. In 1629 he joined the Massachusetts Bay Company, which sailed to New England in 1630 to establish a new commonwealth. He was also a lay preacher whose most famous sermon, “A Modell of Christian Charity,” was composed on board the Arabella during his transatlantic crossing. This sermon outlined his aspirations for the new colony to be a “city on a hill” which would serve as a model of godly governance and brotherly love.

Winthrop was Governor of Massachusetts for twelve one-year terms. When not serving as Governor, he still exercised influence as deputy governor or as a member of the board of magistrates.

He testified against Anne Hutchinson* when she was tried before the General Court in 1637 and was instrumental in securing her banishment from Massachusetts in 1638.

He helped to write the Massachusetts Body of Liberties in 1641, which outlined the legal rights of citizens of the Massachusetts colony, and legalized slavery there.

Winthrop died in 1649. His journal, which recorded events in the colony from 1630 to 1649 and was published posthumously as A History of New England, remains one of the most important historical sources of information on the early Massachusetts colony.