West of the Imagination

Professor Franklin Speyers remembers watching Gene Autry on his neighbors’ black-and-white TV in 1956 in Chatham, Ontario, Canada, after immigrating from the Netherlands with his family a few weeks earlier. He became captivated by everything about the West.

“I couldn’t understand a word of English, but as a stranger in a strange land, yet I was drawn into an enigmatic kinship with a genre that dramatized the triumph of the self-reliant lone hero overcoming conflict… I’m a wannabe Westerner. When I’m in the West, I see more clearly. I think more simply. I’m energized and refreshed. I’m me.”

Speyers has carried this love of the West with him ever since, and will display that love through 30 oil paintings at Calvin’s Center Art Gallery in the Covenant Fine Arts Center from October 26 to December 30. All 30 paintings will be accompanied by their original drawings as well.

Inspired by the West

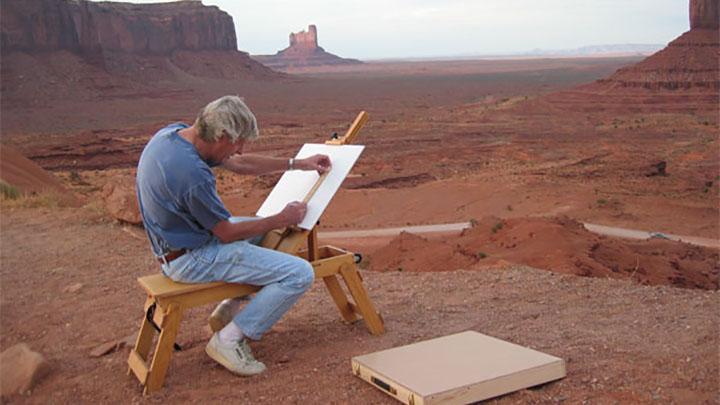

Speyers began working on his 30 Western paintings in summer 2015, but he has been an avid plein air painter all his life; in fact, his first plein air painting venture was in 1962 with a pair of onions next to his bed and then a scene from Medway Creek in London, Ontario as the subject matter.

After he began teaching graphic design in Calvin’s art and art history department in 1988, he encountered Native Americans for the first time in 1993 in Tuba City, Arizona, on vacation with his wife Bonnie and sons Joshua and Jonathan.

“My initial encounter with the Navajo on our family excursion to Monument Valley was very moving,” he said. “From movies, I was conditioned to accept the stereotypical images of Sioux, Cheyenne and Navajo as warlike people. In person, I found them to be gracious and gentle, eager to dialogue and be understood.”

The first cowboy Speyers painted was Grant Shearer, in whom he saw the West that most resonated with his immediate imagination. It was conversations with Chief David Bald Eagle and Chief Thomas White Eagle that left the greatest impression on Speyers, though. Chief Dave Bald Eagle, who fought in World War II and wore a World War II baseball cap, represented everything Speyers loved about the West as a man that knew about conflict and how to straddle cultures.

Design as language

At Calvin, Speyers teaches design as language. He gained this perspective after working with Massimo Vignelli, an Italian designer during his postgraduate studies at Harvard University Graduate School of Design (1990-1992). What he learned he directly incorporated into his rubrics for his Calvin classes. “Working with Massimo clarified that graphics is not just software literacy nor organizing information; it is linguistic and can be comfortably positioned within a semiotic rubric,” he said.

After pushing pixels for 25 years, Speyers found fresh inspiration in the discipline of plein air painting. “There’s something wonderfully satisfying in working with stuff and getting your hands dirty. If I stay too long in the world of pixels, I find myself longing for stuff. I need to get outside,” he said. “Plein air painting is indeed a reaction to the world of dancing pixels. Come out onto the prairie grasses of Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas, and wow—stand and feel overwhelmed by the quietude of the landscape and the huge sky. It’s deeply transcendent.”

Hopes for the exhibit and beyond

Speyers learned to deal with many questions during his time visiting and painting cowboys and Native Americans: How do you treat people from different backgrounds than yours? How do you dialogue with people that have different views than yours? And what kinds of suppositions do they hold to that you can tap into?

Since his work was published in the 2017 August/September issue of Cowboys & Indians magazine, Speyers has received many requests from folks out West who want his work and workshops. “My work has given me a platform to go out West and talk about the things I’m passionate about out there—it’s been really exciting,” he said.

He plans to continue working in the large sky motif as he has historically, but his sons have also encouraged him to revisit biblical themes in his work. “As you become older, you become cognizant that you have very limited time, so you become more preoccupied with the remaining strength you have to leave something behind for the context you’re in and the generations ahead,” Speyers said.

The opening reception for Speyers’ exhibit will be held on October 28.