Wild Hope: Stories for Lent from the Vanishing

When the hibernations of winter are over, Christian tradition offers Lent. The season means to rouse us from our self absorption, to wake us to the true state of our hearts and the world we’ve made. Today, species like the black-footed ferret are vanishing at a rate at least 100 times faster than in the past, because of the choices we humans make. Startled awake to that fact, we also wake to an aching, wild hope that something new might be born of the ruin. Is resurrection possible? The promise of Lent is that resurrection is at loose everywhere in the world, surging wherever hearts break open in a larger compassion.

bodyimage1

callout1

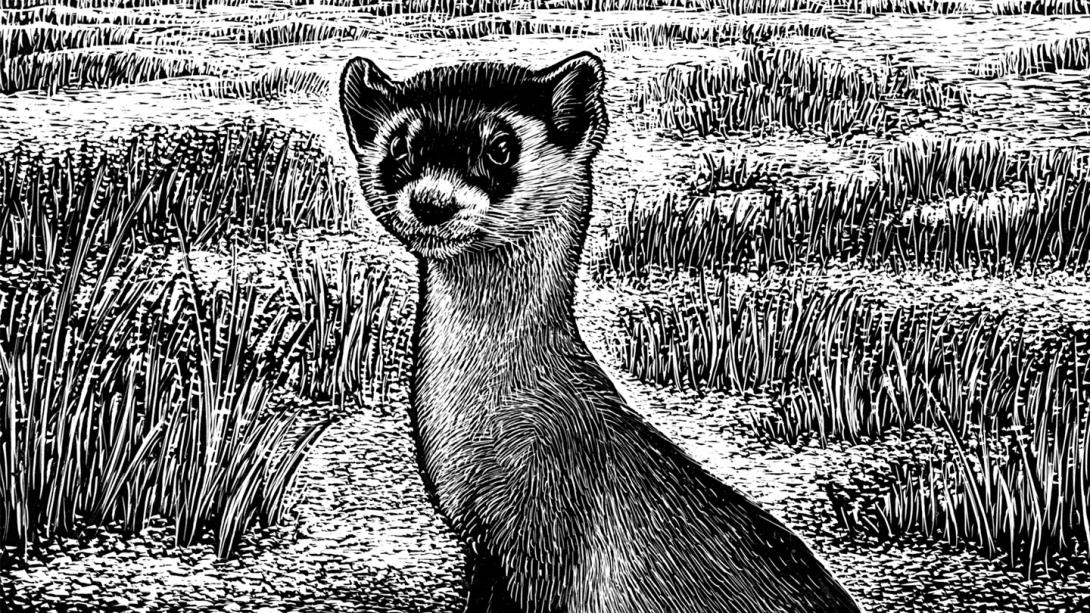

Black-Footed Ferret

On a mound of dirt on a wind-combed prairie in northern Wyoming, the rarest mammal in North America is dancing. He prances and bucks then stops. Then hops—forward, forward, backward, side-hop left—spins around, and dives into the hole at the center of the mound. A four-beat wait. His black bandit mask peeks over the rim. Then he flings the muscular tube of his torso out again into the prairie dawn, bounding, twisting, frisking for an audience of none.

He is fully grown, an adult, not a play-inclined kit. His jaunty moves are not meant to confuse predator or prey, attract a mate, or warn companions. The only reason for his dance is ferret-ness. Curious and quick, lithe and strong, black-footed ferrets often dance just because they are, just because they can.

Audaciously alive, this ferret ends his dance as the sun rises and slips underground to sleep away the day in a burrow that a prairie dog clan abandoned. His short fur and slender shape insulate him poorly against prairie cold; he needs the reliable warmth of their underground home. It’s his hermitage now, a base from which he’ll range a mile or more in the dark of the March night, looking for the emerald eyeshine of a female willing to mate in the nearest empty prairie dog den. Because he ate last night—catching a prairie dog asleep, killing it cleanly with a bite to the windpipe—he has food cached away for two more days. Besides food, prairie dogs supply another essential for a ferret on the hunt. Should a badger, coyote, or bobcat target his emerald eyeshine and pounce, prairie dog holes provide his surest escape hatch.

For nearly a million years, prairie dogs and ferrets lived together well in the heart of North America. Prairie dogs fed ferrets and sheltered them. Ferrets culled prairie dog colonies to a size the land could support. Both communities thrived. At one time a million black-footed ferrets lived among hundreds of millions of prairie dogs on grasslands that stretched between Saskatchewan and Mexico.

Within 150 years the prairie dog towns were plowed up or poisoned. To the pioneers planting crops and grazing livestock to feed the growing hunger of a growing nation, prairie dogs were competitors for the rich land. By 1980, a mere 2 percent were left, holding on in small colonies cut off from each other. As prairie dogs go, so go ferrets—faster. By 1980, nobody had seen one of the wild dancers for six years. Biologists considered them extinct in the wild.

bodyimage2

The following year a Wyoming ranch dog named Shep brought a dead black-footed ferret to his owners’ door. Biologists converged on the ranch, sweeping flashlights across its thousands of acres by night, searching for emerald eyeshine. They found 129 of the extinct species alive and multiplying among the prairie dogs of two neighboring ranches.

Then in 1985, distemper and sylvatic plague—a flea-borne disease brought to North America from Asia—infested the ranches’ prairie dog towns. A plague-infected prairie dog is certain to die. The biologists watching knew that as prairie dogs go, so go ferrets—faster. For two years, they spent their nights trapping the ferrets that had not yet fallen to the plague ravaging their prairie dog hosts. On a cold night in February 1987, they caught the last wild black-footed ferret, a large male they named “Scarface,” and took him away in a pickup truck.

The risk these biologists had taken excited them and terrified them. Had they rescued the world’s eighteen remaining black-footed ferrets from certain death in the wild only to watch them die in cages? No one had successfully bred the creatures in captivity. They worked slowly, methodically, consulting every known expert. They hoped. Some prayed.

In the spring of 1987, Scarface fathered two litters of kits. Since then, nine thousand black-footed ferrets have been born in carefully controlled captivity, and most of those have been released into prairie dog towns at sites across the West—including the ranch that was home to Scarface. It is his descendant now dancing there at dawn.

He doesn’t know his survival chances are slim. He is still the rarest mammal in North America, and is apt to be, until prairie dogs receive some measure of the devotion that has saved him. Researchers, understanding the symbiosis of the two species, have developed a peanut butter-flavored vaccine that prairie dogs love and that makes them immune to sylvatic plague. That means ferrets too are spared—if nearly all the prairie dogs at a ferret-release site eat a vaccine. How to be sure every prairie dog takes his peanut butter-flavored medicine is biologists’ next feat.

But all the efforts to protect prairie dogs in order to protect ferrets will work only if farmers and ranchers choose to see the dogs differently. The owners of this ranch have. When they described how a cattle operation works, conservationists listened and eased restrictions on what they could and could not do on their land. Ranchers listened when conservationists described prairie dogs as not only hosts extraordinaire for ferrets, but also as the anchors of an intricately ordered homeplace for more than one hundred species found nowhere else on Earth. At the end of the conversation, the ranchers asked to have black-footed ferrets brought home to the land from which their 18 ancestors were taken. Pledging to protect the ferrets, they’ve pledged to respect the prairie dogs. They are, they see, a new kind of pioneer.

Gayle Boss is also the author of All Creation Waits: The Advent Mystery of New Beginnings. She and her husband, Doug Koopman, are the parents of two Calvin alumni.