In 1990, I spent a sabbatical year with my family in the German city of Cologne. Despite all the things that make living in a foreign country difficult, it was for us a year of unalloyed urban joy. We did not own a car. But that didn’t matter in the least. I rode a bike to the university. The church we attended was just a four-block walk from our apartment. The elementary school my children went to was also close by and required no bus. The main street of our neighborhood, three blocks away, offered all we needed on a daily basis— a grocery store, a bakery, a flower shop, a newsstand, a stationery store, two bookstores and several restaurants. The Stadtwald—a 10-mile-long park that rings the western edge of the city—was just a 10-minute walk along a pleasant canal, putting playgrounds, tennis courts, tearooms, lakes with boat rentals and, most importantly, ice-cream vendors within our family’s pedestrian reach.

On weekends we often took the bus downtown. On the plaza before the great Cologne cathedral there was always something free and festive going on—church choirs, street musicians, sidewalk artists, magicians, mimes and acrobats. On top of that, there were no neighborhoods to avoid. There were no crime-ridden slums. German society may have its share of problems, but putting together humane, coherent and delightful cities is not one of them.

How painful to return home and be reminded of the sorry state of the urban fabric in North America. So many of our inner cities have been abandoned, converted into dead zones, warehouses for those too poor to leave, their streets mean and shabby, their buildings vandalized, their stores boarded up, their schools closed, permeated by an atmosphere of fear and despair.

When people ask me how I got interested in urban issues, my short answer is: “I grew up in LA.” My long answer is that I grew up in Fullerton, in Orange County, about 35 miles southeast of LA, during the 1960s. At the beginning of that decade, Orange County was a collection of distinct towns surrounded by orange groves and bean fields. My father owned a drugstore on Harbor Boulevard, the main street of Fullerton, which would take you to Newport Beach after a half-hour drive to the south. As a child I performed a variety of menial jobs in the store, often pausing to listen to conversations my father held with his regular customers, who also seemed like his friends. Lives were shared; local affairs discussed.

By the mid-1960s, the character of the region was changing rapidly. A carpet of housing subdivisions, shopping malls, parking lots, freeways and gas stations was being rolled out from LA. Soon the orange groves and bean fields disappeared, and Orange County became one vast undifferentiated conurbation. It was difficult to tell when you left one town and entered another. The towns themselves had been gutted as retail moved out to the malls. At the end of his career, my father worked for a chain drugstore in a supermarket far removed from his place of residence. His customers were strangers to him. Just about all traces of civic life and identity, it seemed, had evaporated.

Paying attention to the fabric of our neighborhoods...can help us address presssing issues of segregation, affordability, civic engagement and sustainability.

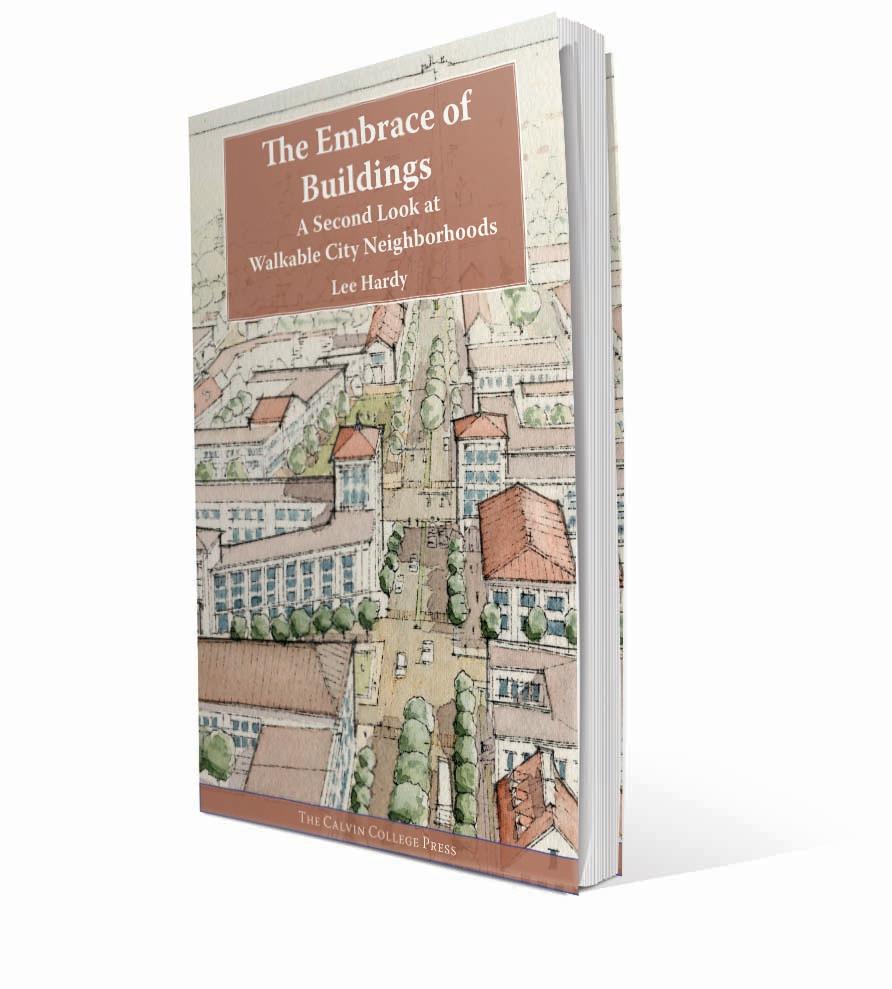

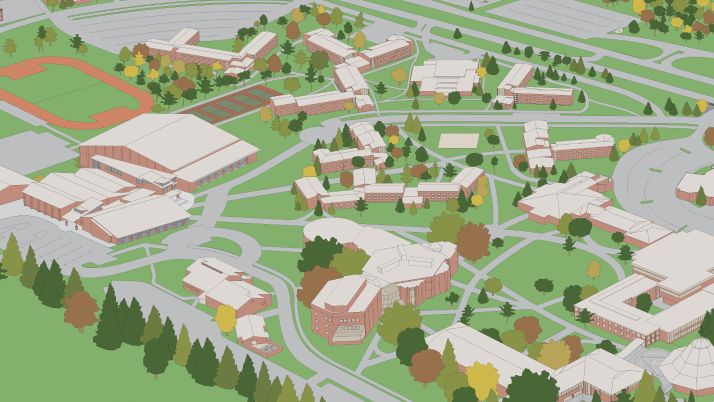

I am a philosopher by training. But I have devoted many years to studying urban design and the dissolution of human-scaled neighborhoods, especially after the Second World War. Much of my new book is drawn from an interim course on urbanism I’ve taught for the last 10 years at Calvin.

I, like you, live in a real place, not in my mind. But my students and I have discovered that we can draw on our intellectual resources to address issues that affect the common good. We need not choose between deteriorating urban cores and degraded suburban landscapes. In fact, paying attention to the fabric of our neighborhoods—our street designs, our public transportation systems, our zoning ordinances, the location and size of our churches and other practical details—can help us address pressing issues of segregation, affordability, civic engagement and sustainability. It may indeed be time to appreciate the embrace of buildings and take a second look at walkable city neighborhoods.