In school, Greg Dykstra ex’87 aspired to do big architecture—universities, art museums—buildings that showed up in glossy architecture magazines. Until, quite by chance, he was presented with an architecture option he’d never imagined.

“It’s like playing with little cities every day,” he said, “cities with hundreds of different kinds of inhabitants. The problem solving is endless.”

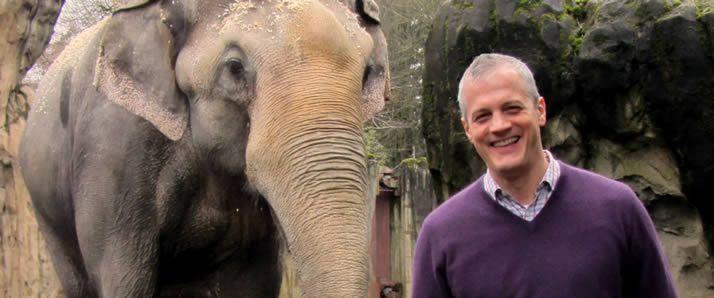

Dykstra designs zoos, or components of them. He’s a principal at CLR Design in Philadelphia, which since its founding in 1984 has focused on enhancing the zoo experience for both animals and their human guests.

It began with gorillas. They’d been kept, from the time zoos were built, behind bars, usually in tiled rooms.

“There was nothing enlightening about that,” Dykstra explained. “The founders of our firm visited the natural habitats of gorillas and said, ‘There’s no reason we can’t re-create that in zoos.’ They called it ‘landscape immersion.’ The visitor becomes deferential to the animal, immersed in its environment.”

The company, which Dykstra joined in the mid-’90s, has continued to lead the evolution of zoos.

“Now we’re pushing ‘activity-based design,’” he said, “design that encourages more of the natural behaviors animals would exhibit in the wild.”

In the African savannah exhibit Dykstra and CLR designed for the Dallas Zoo—which won a 2011 Significant Achievement Award from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA)—elephants, giraffes, ostriches, impalas and zebras all mingle in a four-acre tract.

“The animals find their own corners or chase and play or sniff each other, coexisting very well,” Dykstra said. “For the animals and the guests it creates a more dynamic place to be.”

Helping zoos break the one-animal/one-exhibit mold in favor of flexible, dynamic environments is a collaborative process that Dykstra loves to lead.

“We listen to what the zoo wants and its limitations—budget, space, staff. Then, because of all our prior experience, we can be the provocateurs, pushing, encouraging them to explore innovative options.”

When zoo and provocateur become robust partners, everybody wins.

Record numbers showed up at the gates of the Denver Zoo last June for the opening of the Dykstra-designed Toyota Elephant Passage—10 acres of housing, outdoor yards, bridge crossings and pools deep enough for the four resident pachyderms to have full-immersion baths. The construction earned the LEED Platinum certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. Even more forward thinking is the new waste-to-energy system Dykstra and zoo staff designed. Called “gasification,” it converts all zoo waste—from food wrappers to animal droppings—into clean energy. For its sustainability practices the AZA has ranked Denver’s the greenest zoo in the country.

“The AZA likes to say that each year in the U.S., more people visit zoos than attend all professional sporting events combined,” Dykstra said. “That’s an immense audience to reach with the message of being good stewards of the earth. It’s all connected: conserving resources, conserving habitat, conserving animals.”

Visitors to Grand Rapids’ John Ball Zoo will soon be able to see Dykstra’s design. By summer the bears there will enjoy a larger, recirculating pool set in a larger space with plants and sand instead of their 50-year-old concrete grotto.

“What I hope is that our designs can inspire guests to care,” he said. “Maybe some kid visiting the zoo is a future conservationist or scientist, someone who would say, ‘My childhood zoo inspired me to take action.’”